South African chemical giant Sasol became embroiled in allegations of industrial espionage and sabotage against environmental activists, when Greenpeace took an American subsidiary to the Federal Court in Washington, DC.

Other respondents in the case include The Dow Chemical Company and two public relations firms.

Greenpeace accuses Sasol North America and Dow of hiring private investigators to steal its documents, tap its phones and hack into its computers between 1998 and 2000.

It is suing for damages, which it says should be established by a jury. Central to the complaint is a community’s battle against the pollution of Lake Charles, in Louisiana, near the Sasol plant.

Greenpeace claims that local residents suffer high rates of cancer and respiratory problems linked to the company’s production processes.

It claims that the two chemical companies, though their PR agencies, hired a security firm to keep tabs on it and the campaigns it was conducting.

At issue is whether Sasol can be held liable for the alleged sins of a company in which it invested. The Louisiana plant became part of the Sasol stable only in 2001, after the alleged espionage took place.

The chemicals

According to Sasol’s website the Lake Charles plant produces commodity and speciality chemicals for soaps, detergents and personal care products.

At the time of the Greenpeace complaint, it was manufacturing ethylene dichloride, a suspected carcinogen, and vinyl chloride.

CONTINUES BELOW

Sasol North America operates as part of Sasol Olefins Surfactants, headquartered in Germany, which is, in turn, part of the chemicals division of Sasol Limited.

“At the time referred to in the Greenpeace complaint the company in question was named Condea Vista Inc and was not owned by Sasol,” said Sasol Group communications chief Jacqui O’Sullivan this week.

O’Sullivan said Sasol acquired Condea Vista in March 2001. “The alleged … espionage relates to a time period more than 10 years ago,” she said.

Condea Vista allegedly leaked up to 21 000 metric tonnes of ethylene dichloride into the Calcasieu River in Louisiana in 1994, sparking an intensive environmental campaign. The area was the subject of an environmental investigation in 2001.

Evidence that Greenpeace plans to use in the lawsuit includes files from security firm Beckett Brown International, consisting of daily logs, emails, reports and phone records.

The 56-page lawsuit alleges that Beckett agents infiltrated a Louisiana community group concerned about the plant’s activities and conducted “surveillance and intrusion” against employees at the plant, as well as community members.

Greenpeace’s claims

The security firm’s agents also allegedly obtained Greenpeace activists’ phone records and sorted through their rubbish.

Greenpeace claims off-duty police officers and former American National Security Agency computer security experts stole thousands of confidential documents from the activists, including campaign plans.

Greenpeace claims Beckett’s billing records show that it spent hundreds of hours spying on it.

“Beckett Brown International identifies Greenpeace as a ‘target’ and, in a 1998 memorandum describing its activities to monitor ‘environmental activist groups’, stated that the information being obtained by Beckett ‘provides insight into the scheduling of environmental protests and actions of the group, corporate targets, the tracking of maritime cargo by the group and internal political issues of the group’,” court papers say.

Philip Radford, executive director of Greenpeace, wrote in his blog that the first purpose of the lawsuit was “to put a dent in the arrogance of these corporate renegades who have for too long believed that ethics do not apply to their pursuit of ever-higher profits”.

“Second, we believe it is every citizen’s right to stand up for the health of their children and community without fearing retribution, an invasion of privacy, conspiracy against them or theft of their belongings.

“We believe Dow and Sasol conspired to do this to Greenpeace; we aim to stop this before it happens to you.”

Greenpeace claims that the public relations firms involved — including Nichols-Dezenhall and Ketchum — acted as middlemen between the chemical companies and Beckett.

Greenpeace apparently smelled a rat when an investigative piece in American magazine Mother Jones in 2008 hinted that Beckett was spying on activists in Louisiana.

The article lifted the lid on the company’s far-flung activities, including work for Walmart, Halliburton and Monsanto. Beckett has since been disbanded.

Lawyers from across the government are investigating whether it can prosecute WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange for espionage, a senior defense official said Tuesday.

The official, not authorized to comment publicly, spoke only on condition of anonymity.

The decision is complicated by the very newness of Assange’s Internet- based outfit: Is it journalism or espionage or something in between?

Other charges also might be possible, including theft of government property or receipt of stolen government property.

By Pete Yost

The government’s decisions about whether or how to bring criminal charges against participants in the WikiLeaks disclosures are complicated by the very newness of Julian Assange’s Internet-based outfit: Is it journalism or espionage or something in between?

Justice, State and Defense Department lawyers are discussing whether it might be possible to prosecute the WikiLeaks founder and others under the Espionage Act, a senior defense official said Tuesday.

They are debating whether the Espionage Act applies, and to whom, according to this official, who spoke anonymously to discuss an ongoing criminal investigation. Other charges also might be possible, including theft of government property or receipt of stolen government property.

Rep. Peter King of New York called for Assange to be charged under the Espionage Act and asked whether WikiLeaks can be designated a terrorist organisation.

But Assange has portrayed himself as a crusading journalist: He told ABC News by e-mail that his latest batch of State Department documents would expose “lying, corrupt and murderous leadership from Bahrain to Brazil.” He told Time magazine he targets only “organisations that use secrecy to conceal unjust behavior.”

Longtime Washington lawyer Plato Cacheris, who represented CIA official Aldrich Ames and other espionage defendants, said Tuesday that Assange could argue he is protected by the First Amendment, a freedom of the press defense. “That would be one, certainly,” Cacheris said.

Constrained by the First Amendment’s free press guarantees, the Justice Department has steered clear of prosecuting journalists for publishing leaked secrets. Leakers have occasionally been prosecuted, usually government workers charged under easier-to-prove statutes criminalising the mishandling of classified documents.

But two leakers faced Espionage Act charges, with mixed results.

The last leak that approached the size of the WikiLeaks releases was the Pentagon Papers during the Nixon administration.

The Supreme Court slapped down President Richard Nixon’s effort to stop newspapers from publishing those papers. But the leaker, ex-Pentagon analyst Daniel Ellsberg, was charged under the Espionage Act with unauthorised possession and theft of the papers.

A federal judge threw out the charges because of government misconduct including burglary of Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s files by the White House “plumbers” unit.

The Reagan administration had more success against Samuel Loring Morison, a civilian intelligence analyst for the Navy and grandson of a famous US historian. Morison was convicted under the Espionage Act and of theft of government property for supplying a British publication, Jane’s Defence Weekly, with a US satellite photo of a Russian aircraft carrier under construction in a Black Sea port. Dozens of news organisations filed friend-of-the-court briefs supporting Morison because he was a $5,000-a-year part-time editor with Jane’s sister publication and thus arguably a journalist.

But WikiLeaks has entered a space where no journalist has gone before. News organisations have often sought information, including government secrets, for specific stories and printed secrets that government workers delivered to them, but none has matched Assange’s open worldwide invitation to send him any secret or confidential information a source can lay hands on.

Is WikiLeaks the leaker or merely the publisher?

“The courts have been somewhat reluctant to draw a line of demarcation between what we call mainstream media and everyone else,” said Washington attorney Stan Brand. “If these people are publishing and exercising First Amendment rights, I don’t know why they’re less entitled to their First Amendment rights to publish.”

But at a news conference Monday, Attorney General Eric Holder contrasted WikiLeaks with traditional news organisations, which he said acted responsibly in the matter even though several posted some classified material. Some news organisations consulted with the government in advance to avoid printing harmful material; Assange has claimed his efforts to do likewise were rebuffed.

“One can compare the way in which the various news organisations that have been involved in this have acted as opposed to the way in which WikiLeaks has,” said Holder.

Some see openings for the government.

Assange “has gone a long way down the road of talking himself into a possible violation of the Espionage Act,” First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams said on National Public Radio, noting that Assange has said leaks could bring down a US administration.

Washington lawyer Bob Bittman expressed surprise the Justice Department has not already charged Assange under the Espionage Act and with theft of government property over his earlier release of classified documents about US military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. Bittman said it was widely believed those disclosures harmed US national security, in particular US intelligence sources and methods, meeting the requirement in several sections of the act that there be either intent or reason to believe disclosure could injure the United States.

“These are not easy questions,” said Washington lawyer Stephen Ryan, a former assistant US attorney and former Senate Government Affairs Committee general counsel. Ryan said it would be legally respectable to argue Assange is a journalist protected by the First Amendment and never had a duty to protect US secrets.

But Ryan added, “The flip side is whether he could be charged with aiding and abetting or conspiracy with an individual who did have a duty to protect those secrets.”

On the question of conspiracy there’s a legal difference between being a passive recipient of leaked material and being a prime mover egging on a prospective leaker, legal experts say.

Much could depend on what the investigation uncovers.

Army Pfc. Bradley Manning is being held in a maximum-security military brig at Quantico, Va., charged with leaking video of a 2007 US Apache helicopter attack in Baghdad that killed a Reuters news photographer and his driver. WikiLeaks posted the video on its website in April.

Military investigators say Manning is a person of interest in the leak of nearly 77,000 Afghan war records WikiLeaks published online in July. Though Manning has not been charged in the latest release of internal US government documents, WikiLeaks has hailed him as a hero.

Another obstacle would be getting Assange to the United States. His whereabouts are not publicly known.

In France, Interpol placed Assange on its most-wanted list Tuesday after Sweden issued an arrest warrant against him as part of a drawn-out rape probe – involving allegations he has denied. The Interpol “red notice” is likely to make international travel more difficult for him.

But even if Assange were charged and arrested in a country that has an extradition treaty with the United States, there could be problems getting him here. The Espionage Act carries a maximum penalty of death, and nations with no death penalty often refuse to send defendants here if they face possible execution.

One renowned First Amendment and national security lawyer, Duke law professor emeritus Michael Tigar urged caution.

“The US reaction to all of this is rather overblown,” Tigar said. “One should hesitate a long time before bringing a prosecution in a case like this. The First Amendment means that sometimes public expression makes the government squirm. … That diplomats collect information, and are sometimes brutally candid, comes as no surprise to anybody.”

(This version corrects grammar in 1st paragraph, changing “is” to “are.”)

AP

TX – A Springtown man has been accused by police of recording a video of an 18-year-old woman showering at his home while using a “spy pen” without her consent.

A second-grade teacher at a Fort Worth elementary school, Brian Paul Weaver, 38, turned himself in to authorities and is charged with improper visual recording without consent, according to a Springtown Police affidavit.

A second-grade teacher at a Fort Worth elementary school, Brian Paul Weaver, 38, turned himself in to authorities and is charged with improper visual recording without consent, according to a Springtown Police affidavit.

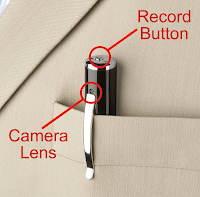

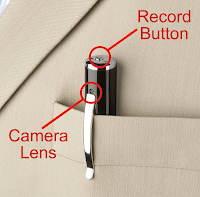

The “spy pen,” which functions as a pen with a camera attached, was taken by one of Weaver’s children to school, where it was discovered by another student and given to a teacher, Sgt. Shawn Owens of the Springtown Police Department said.

“One of the children in Brian Weaver’s home took the pen to school thinking it was just a pen, and that’s where at the school it was discovered as more than just a pen,” Owens said. (more)